Page 17 of 25

Comparison of Mother, Father, and Teacher Reports of ADHD Core Symptoms in a Sample of Child Psychiatric Outpatients

Review by Ron Huxley

A study in the Journal of Attention Disorders looked at the differences or similarities of identifying ADHD symptoms in children between Fathers, Mothers and Teachers. It didn’t surprise me that fathers reported fewer symptoms than did mom and dads. This is probably due to the fact that dads, typically, spend less time with children than do moms and teachers. It isn’t a gender issue as a teacher could easily be a man as well as a women. Having said that, parental roles played out by gender may have some influence over what is noticed and what is not. The interesting finding of the study was that moms and dads correctly diagnosed the problem at the same rating. Apparently, dads can spot ADHD when they see it – the question, I suppose, is do they see it.

Share your thoughts on this by posting a comment here or at our Facebook page or on our Twitter Stream.

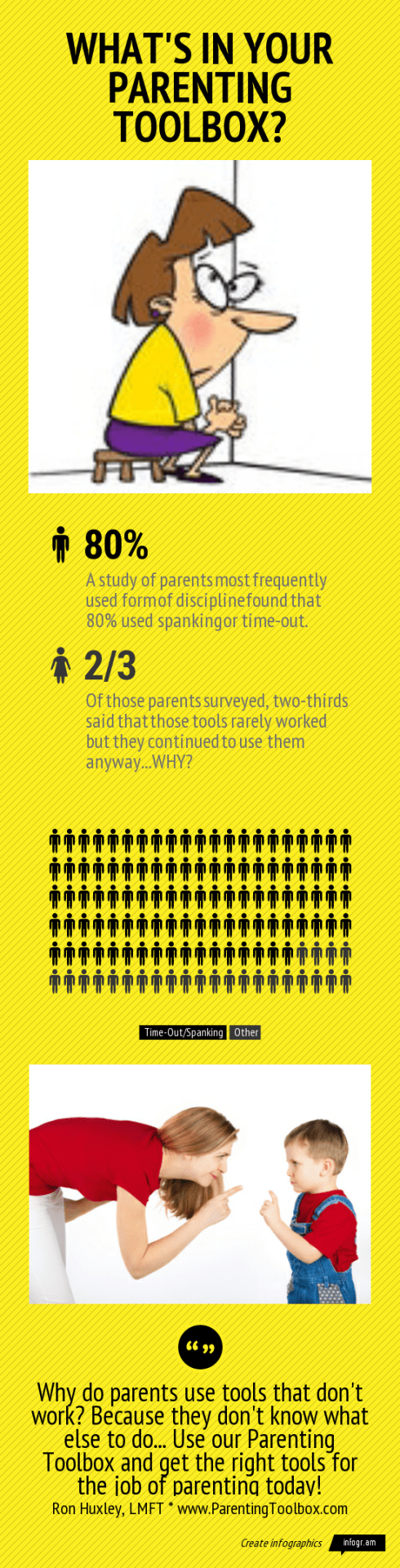

What is in your Parenting Toolbox? A study on the most widely used parenting tool revealed that most parents use time-out or spanking to discipline their children. When asked how effective their primary tool was only 1/3 stated that it worked consistently for them. That left 66.9% that felt it didn’t work. Why use a tool that doesn’t work? Because parents don’t know what else to do…

This is the mission and goal of the Ron Huxley’s Parenting Toolbox: To give parents the right tools to do the job of parenting.

What works for you? Share with us by clicking the comment button or go to Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/parentingtoolbox

or share with us on twitter at http://www.twitter.com/ronhuxley

“He Never Acts This Way At School!”

By Ron Huxley

“The energy which makes a child hard to manage is the energy which afterward makes him a manager of life.” – Henry Ward Beecher"

by Ron Huxley, LMFT

Have you ever heard a parent say this or perhaps said it yourself? Why do some children misbehave at home and not other settings, like school? While the opposite situation might be true, where the child misbehaves at school and not home, let’s look at this common parenting frustration.

Teaching is a good definition of balanced discipline. In fact, the word discipline comes from the root word “disciplinare”, which means to teach or instruct. Most parents understand discipline as reducing inappropriate behaviors (punishment) instead of helping children achieve competence, self-control, self-direction, and social skills. Of course, all parents want this. But reinforcing appropriate behaviors seems like a luxury or fantasy when parents are having problems with their children. One reason for this may be the act of juggling work and family that so many contemporary parents find themselves performing. In this situation, only the most annoying or irritating behaviors are sure to get a parents attention. Children quickly learn that good behavior or even quiet, self-directed behavior rarely gets the attention of overloaded parents. Good behavior is one less thing a parent has to deal with while bad behavior guarantee parents attention. This is what educators and therapists call “negative attention” – a powerful reinforcer of children’s misbehavior.

So when parents say their child doesn’t misbehave in school, perhaps we should investigate the school/teaching model a little closer to see what frustrated parents can use when disciplining their children. Of course, as any teacher will admit, perfect behavior from children never occurs at school or anywhere else. But, let’s compare school behaviors to home discipline and ask a few questions.

Schools are learning environments. Discipline requires a learning environment characterized by positive, nurturing parent-child relationships. Is your home a learning environment or an entertainment center? Are their books, activities and private spaces for children?

Teachers use a curriculum. Discipline occurs when a plan or structure is in place for children. Do you know what you want to teach your children? What values or ideas do you want your children to believe? Is there a set time or routine for learning these things? Are you available to the child for help and instruction? Do you have materials available to educate you about topics you want to teach your children? Are there regular discussions about daily responsibilities, spiritual ideas, personal dreams, and problem areas? Grades are used to evaluate a child’s progress in school. Discipline can be both an instruction and a measurement of children’s behavior. What grade would you give your child in hygiene, social ability, responsibility, etc.? What rewards (physical or verbal) are given for “A” grades? Are parent-child conferences held to discuss strengths and weaknesses and make a plan for improvement? Do children get regular feedback from parents on how they are doing at home?

Teachers are in charge of the classroom and model appropriate behavior. Discipline is most effective when parents remember that they are the leaders of the home and “practice what they preach.” Are you firm and consistent in your discipline with your children? Do you model appropriate behavior for your children? Do you give the things, to your children, that you ask for, from your children, such as respect? Do you say what you mean rather than threaten or bribe children? Do you have a list of rules posted where children can see them? Do you allow children to “raise their hands” and ask questions? Do you listen attentively to those questions and give an appropriate answer?

Children, in schools, are given opportunities to explore and understand the world and themselves. Discipline is about internal control and not just external control. Do you give your child choices that require him or her to think about consequence? Are children recognized for behaving in an appropriate manner? Are there any “field trips” that children go on to inspire, instruct, or experience appropriate behavior? Are children give opportunities to act in a responsible and trustworthy manner? Are children encouraged to help their siblings and work as teams? Are there any parties for celebrating hard work?

Classrooms have rules that children must follow. Are their assigned seats at the dinner table or car? Are there any rules about waiting, talking, and seeking help? Do children get to “line up first” or “pass out the snacks” for exemplary behaviors? Are consequences given for inappropriate behaviors? Do children get warnings about misbehavior? Do children get to go to recess when they misbehave? Are the rules discussed with the children, posted where everyone can see them, and frequently reviewed?

Schools have recesses, school holidays, and summer breaks. Discipline is about doing nothing as much as it is about doing something. Do you allow your child to make mistakes and decide difficult (but not dangerous) situations on their own? Are there healthy balances between fun and chores, rest and responsibilities, work-time and playtime? Do you allow your child to simply be a child? Are developmental expectations appropriate to the age and abilities of your child? Do you allow yourself to be off-duty by having other adults to watch over your children? Are plans made, in family meetings, for fun as a family? Is quality time a regular part of your time with your children?

While this may not cover all aspects of school routines or discipline practices, it does ask some very reflective questions. It is possible we missed the most basic reason for children’s different behaviors, namely, novel situations and conditional love. Novel situations refer to a phenomenon that affects a child’s behavior, for good, when in a new environment. A new environment is unpredictable and may require a child to be on his or her best behavior until the child learns what the rules and consequences are or what they can get away with. Home is often predictable. The child already knows what they can or cannot get away with.

Conditional love refers to the communication of worth a child will get from another individual based on their behavior. A teacher may only consider certain behaviors to be worthy of his or her love and care. At the root, this is a good strategy. It advocates reinforcing only positive behaviors and ignoring negative behavior. But the fruit of it can have devastating consequences for children’s self esteem. A child’s sense of self should never be based on conditions. A child is worthy of love, dignity, and worth regardless of what they do. Reinforcement and even approval can be placed on a child’s behavior to communicate what is appropriate or inappropriate. A child may not feel this conditional love at home, knowing that mom will always love him or her and so manipulate this to their advantage.

Take a few moments to review these questions. If you are one of those parents who have said, “My child never behaves this way at school?” maybe now, you can finally find out why, and be able to say your child behaves appropriately at home as well as school.

International Adoption: a local family’s story of growing By Stephanie Robusto CONWAY, SC (WMBF) – After reading about the orphan crisis in Africa, it didn’t take the Crawford family long to decide to adopt from Ethiopia. But their journey is far from over. “Our motivation was never if we could have biological or not, it was more than that,” explained Victor Crawford, the proud father of two boys. They explain part of their reason was simple human nature. “We evaluated what our faith really looks like in the real world. Showing compassion and love, that’s our motivation,” said Crawford.

Another reason for adopting internationally came from Crawford spending time abroad during a mission trip. Adoption wasn’t something the couple originally planned on. But spending time in the orphanages of Honduras opened their eyes to an international need. “They have basic needs; a roof, food, and love. We want to provide that,” said Crawford. Now, the Crawford’s are defining what it means to be a blended family. They adopted their first son, Josiah, from Guatemala when he was about 4 years old. A few years later, they had a biological son named Miles. Biological or not, the two boys are brothers. They want to continue growing their blended family. “When Miles got to the age where we thought we could handle another one, we thought ‘let’s start this journey, start this process again,"explained Crawford.

That journey first began here in the states, with the Crawfords trying to adopt in America. "But after three years of no placement, we decided to move forward again with international,” explained Victor’s wife, Robin Crawford. When they learned about the need in Ethiopia, the couple decided to double their family. “We found two brothers, two siblings who needed a home,"said Crawford. "The oldest is 8, the youngest is 3. They’ve been in an orphanage for about 8 months. Their biological father passed away,” explained Mrs. Crawford. Legally, the two boys are already part of the family. But it will be weeks until they are united as a family under one roof.

The waiting has Robin Crawford feeling like an expectant mother. It’s hard for her knowing they are her babies, but she doesn’t have them home with her, yet. “It’s very difficult, it’s something that consumes you all the time,” she expressed. The family recently met the brothers in Ethiopia. They are waiting for the U.S. Embassy to decide a date they can go back again, and hope this time, the boys will be coming back home with them.

To read more about the family, visit their website here:CrawfordsJourney.com Copyright 2013 WMBF News.All rights reserved. Share: / /

Take your parenting measurements…

Does your child have so many problems that you don’t know where to start? Are you so frustrated that you can’t see or think straight? Do you feel helpless about how to make changes in your relationship with your child? Perhaps the first place to start is with a few measurements. When behaviorists study people’s behavior, they start with a baseline.

Baselines:

A baseline is a tool that is used to measure the frequency and duration of someone’s specific behavior. It can be used to measure the frequency and duration of both desirable and undesirable behavior. This dual measurement can tell parents what they want to increase and what they want to decrease, all without a lot of screaming, hair pulling, or medication!

Step 1: Measure without interventions.

The first step in determining a baseline is to measure a child’s behavior when no intervention or tool is being used with the child. This way parents can get an accurate estimation of the child’s behavior. Baselines will allow a parent to measure the effectiveness of a particular parenting tool they are using. If a parent discovers that a tool is not getting the desirable results (i.e., the misbehavior continues at the same level as before or is much worse), then the parent knows to abandon this approach and try another. Parents then find a different tool to use that gets them better results. Sound easy? Actually it isn’t but with a little practice parents can use baselines to objectively and rationally approach a behavior problem and change it.

Step 2: Basic materials and picking a behavior.

The next step is to gather a few basic materials: a piece of graph paper, pencil, and daily calendar. Write across the top of the graph paper the behavior you wish to increase or decrease. For example, you might write: “I want to increase the number of times that Tommy takes his bath on time” or “I want to decrease the number of times that Mary hits her little brother.” Picking the behavior may not be as easy at it sounds. Pick one behavior to focus on and don’t get confused with other problems at home. Be very specific about what you want to increase or decrease. Don’t write: “I want Tommy to behave.” That is too general and vague. You will never achieve that anyway, so why frustrate you and Tommy. If a behavior is extremely troublesome and/or dangerous, that is a good place to start.

To get a baseline, simply count how many times a day that particular behavior is occurring for one week. Average it on a per day basis by taking your weekly total and divide it by seven (days of the week). That will be your baseline.

Let’s say that you want Tommy to take his bath, on time, every day. At this time, Tommy only takes his bath one time per week. One is your baseline. Anything you use to increase this frequency will be considered effective. Anything that does not or reduces it to zero is not effective. After you have picked the behavior, use the bottom of the paper to list the days of the week from the calendar (Sunday, Monday… Saturday). Along the left side of the paper you will write a range of numbers, starting from the bottom and going up. The range could be from zero to ten, if the behavior you are targeting is a low frequency problem or zero to hundred, if it is a high frequency problem. I would suggest sticking with a low frequency problem. It will make the process simpler and easier to monitor.

Step 3: Pick a tool (intervention).

Now comes the fun part: Picking the tool. What will you use to increase or decrease your child’s behavior? You could do what you have always done, like Time-Out or Removing Privileges. You could read up on a couple of books, ask a wise friend or teacher, or search the Internet or download Ron Huxley’s 101 Parenting Tools ebook.

Regardless of where you go for your tools, choose only one! Use the tool of choice for a period of one week and faithfully measure how many times a day that behavior occurs with the application of the tool. Be sure that all caregivers (moms, dads, relatives, day care staff, etc.) use the same tool or you will not get a good measurement. In fact, if dad is doing one thing and mom another, you could be sabotaging each other’s efforts. Get everyone on the bandwagon and cooperating. Chart the number of times the behavior occurs (its frequency per day) and the time that it occurred. In order to see if change has occurred, parents must check to see if there is any difference between the baseline number, before any intervention was made, and the number of occurrences after an intervention is made. This final number should come close to your target number.

Let’s take another look at Tommy and his bath time. Mom and dad decided to take away Tommy’s television privileges if he did not get in the bath on time each day. They did this by simply stating the consequence ten minutes before bath time to give him time to prepare. If Tommy did not get in the bath on time (they gave him a five minute window of opportunity either way) they stated that there would be no television privileges the next morning and stuck to their decision. After a couple of days, Tommy realized that mom and dad were serious about this bath time business and decided to cooperate. He was able to get in the bath, on time, three times in one week, as a result of mom and dad’s new interventions. This was a definite increase from the baseline and considered successful by everyone. Don’t worry if the change doesn’t occur immediately. Children will test their parents to see if they really mean what they say. Consistency is one of the biggest killers of behavioral control in the home. One to two weeks may be needed to witness any real results. If the behavior is still not changing after that period of time, find a new tool. Its just a tool and not a magic wand, to wave over your child’s behavior and make it magically go away.

What if one parent is willing to cooperate but the other is not?

This makes our task harder but not impossible. Simple measure during a time that you are able to control, say, during the daytime when dad is at work. Obviously, you must pick a target behavior that occurs during that time period and find a tool that you can administer alone. Children will adapt to the different parenting styles of their parents, even if they are exact opposites. Reward all positive, behavioral changes. This will help to maintain the behavior over a long period of time. Don’t resort to bribes, such as sweets, money, or toys. This will backfire on you. Use social praise, like: “Great job” or “I really appreciated how you did that.” This is usually sufficient for children. Any negative behavior should be ignored, as much as possible.

How long should you use the baseline tool?

Use the tool for as long as you need. Once you are getting positive results from your new tool, you can go on to targeting a new behavior or put the chart away until it is needed again. Behavior tools, like the baseline, have some limitations. Very smart children see your strategy and try to go around it or do as they are asked, during the specific time it is asked, and then immediately misbehave right after. For example, Tommy may get into the bath on time so that he can watch his favorite television programs, but right after the bath, he may become rude and obnoxious to his little sister. This is a weakness in the tool, not you. Ignore the weakness for now. All you are concerned with is increasing getting into the bath on time. Later you will address, with the baseline tool, the rude behavior. The value of this parenting tool is in its ability to get a baseline measure of a child’s behavior and to test the validity of the parenting tools your are using. It allows you to cope with feelings of frustration and target behavior objectively and without negative attention to the child. This allows the parent and the child to concentrate on more enjoyable activities together.

ParentingToolbox Dream Project: Understanding Your Child’s Behavioral Motivations (by Ron Huxley)

Could Your Child Have Too Much Self-Esteem?

Parenting in the Middle Ground

As with most parenting challenges, we are called upon to strike an all-too-elusive balance between two extremes: the tough love approach, typified by “tiger mom” Amy Chua, who advocates criticism, corporal punishment and name-calling of children who must earn their self-esteem through accomplishments, and the phony praise approach, common among some modern American parents, who cheer their children on whether they’ve earned it or not.

There’s more to effective parenting than either extreme offers. Here are a few ways to find the middle ground:

Keep it Real. High self-esteem isn’t a problem – it’s false self-esteem that knocks kids off course. Instead of applauding your child’s every move, reserve your praise for noteworthy accomplishments and behaviors. Praise should go beyond accomplishments to include personality traits that make your child who they are, such as being a good friend, telling the truth and working hard.

When you do praise your child, be specific and focus on effort rather than the end result. Telling your child you’re proud of all the effort they put in to getting an A on their test is more helpful than saying, “You’re so smart.” Knowing exactly what they did well will enhance your child’s sense of self-worth.

Encourage Strategic Risk-Taking. Self-esteem forms when children challenge themselves. Create opportunities for your child to try new things, and when fears and setbacks arise, encourage them to keep trying rather than giving up or rescuing them.

Acknowledge Strengths and Weaknesses. Children need to know that everyone has strengths and weaknesses. If you pretend your child is great at everything, this may artificially inflate their ego or send the message that perfection is expected – a set-up for low self-esteem.

Embrace Mistakes. Overprotective parents do a disservice to their children’s self-esteem. From mistakes and setbacks children develop resiliency and faith that they are worthy even if they don’t always “win.” Share your own stories of overcoming obstacles and work through problems with your child so they can be successful next time.

Love Unconditionally. Self-esteem flourishes when children know that you will always love and accept them (though you may not always like their behavior or decisions). This message comes through clearly when parents are generous with their affection and listen attentively to their children’s thoughts and feelings.

Reward Social Success. True self-esteem stems from close ties with other people. A 2012 study shows that positive social relationships during youth are better predictors of adult happiness than academic success or financial prosperity. In addition to reinforcing a child’s intellect or athleticism, celebrate their ability to empathize with or help others and encourage them to participate in activities that build social connections.

Avoid Comparisons. Your child needs to be respected for their individual talents and abilities. Resist the temptation to compare your child to their friends or siblings, even if the message is positive. Instead, emphasize your child’s strengths and help them work on their weak spots.

Set Realistically-High Expectations. Children do best when they know what is expected of them. Set clear rules and consequences and follow through when a rule is broken. This predictability lets kids know that discipline and constructive criticism aren’t personal attacks but violations of pre-established rules.

The Byproduct of a Healthy Relationship

The so-called “self-esteem movement” is not a complete abomination. Kids should feel “good enough” and “smart enough,” so long as those sentiments don’t cross the line into “better than” or “smarter than,” particularly if they’re not based on genuine accomplishments and abilities. As parents, this is one area where we can start taking it easy – no more nurturing self-esteem for its own sake but instead doing the things that naturally build self-esteem, like spending quality time as a family.

Dream Parenting: The Natural Ally

At times parenting can be met with rejection by family members. Some of this can be developmental as a child has drives for independence. Some of it can be a self-protection from intimacy. If I don’t get close to you, then I don’t get hurt. Attempts to parent differently and achieve the family of your dreams requires significant risk in these situations.

You biggest ally is already inherent in you and your family members. It is a biologically-based need for attachment. We are social beings and as such, want to connect with one another even it doesn’t appear on the surface to be true.

If there has been problems in your closest relationships it may mean that patterns of rejection and defenses of self-sufficiency have been created. These are tough walls to knock down. Start off by believing that you have a primal need to connect as you ally in this new strategy. Find ways to make eye contact and smile without using any words. Look for chances to connect with no words of judgement, correction, or instruction. Just make a connection no matter how small or brief. Make it a personal challenge to increase these moments everyday until you start to see the walls starting to crumble.

Remember that your family wants this naturally. It was how they are designed. If they don’t get it from you, they will seek it elsewhere but they will find it, good or bad. Make it good starting right now.

Breakthrough study reveals biological basis for sensory processing disorders in kids

Sensory processing disorders (SPD) are more prevalent in children than autism and as common as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, yet it receives far less attention partly because it’s never been recognized as a distinct disease.

In a groundbreaking new study from UC San Francisco, researchers have found that children affected with SPD have quantifiable differences in brain structure, for the first time showing a biological basis for the disease that sets it apart from other neurodevelopmental disorders.

One of the reasons SPD has been overlooked until now is that it often occurs in children who also have ADHD or autism, and the disorders have not been listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual used by psychiatrists and psychologists.

“Until now, SPD hasn’t had a known biological underpinning,” said senior author Pratik Mukherjee, MD, PhD, a professor of radiology and biomedical imaging and bioengineering at UCSF. “Our findings point the way to establishing a biological basis for the disease that can be easily measured and used as a diagnostic tool,” Mukherjee said.

The work is published in the open access online journal NeuroImage:Clinical.

‘Out of Sync’ Kids

Sensory processing disorders affect 5 to 16 percent of school-aged children.

Children with SPD struggle with how to process stimulation, which can cause a wide range of symptoms including hypersensitivity to sound, sight and touch, poor fine motor skills and easy distractibility. Some SPD children cannot tolerate the sound of a vacuum, while others can’t hold a pencil or struggle with social interaction. Furthermore, a sound that one day is an irritant can the next day be sought out. The disease can be baffling for parents and has been a source of much controversy for clinicians, according to the researchers.

“Most people don’t know how to support these kids because they don’t fall into a traditional clinical group,” said Elysa Marco, MD, who led the study along with postdoctoral fellow Julia Owen, PhD. Marco is a cognitive and behavioral child neurologist at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, ranked among the nation’s best and one of California’s top-ranked centers for neurology and other specialties, according to the 2013-2014 U.S. News & World Report Best Children’s Hospitals survey.

“Sometimes they are called the ‘out of sync’ kids. Their language is good, but they seem to have trouble with just about everything else, especially emotional regulation and distraction. In the real world, they’re just less able to process information efficiently, and they get left out and bullied,” said Marco, who treats affected children in her cognitive and behavioral neurology clinic.

“If we can better understand these kids who are falling through the cracks, we will not only help a whole lot of families, but we will better understand sensory processing in general. This work is laying the foundation for expanding our research and clinical evaluation of children with a wide range of neurodevelopmental challenges – stretching beyond autism and ADHD,” she said.

Imaging the Brain’s White Matter

In the study, researchers used an advanced form of MRI called diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which measures the microscopic movement of water molecules within the brain in order to give information about the brain’s white matter tracts. DTI shows the direction of the white matter fibers and the integrity of the white matter. The brain’s white matter is essential for perceiving, thinking and learning.

The study examined 16 boys, between the ages of eight and 11, with SPD but without a diagnosis of autism or prematurity, and compared the results with 24 typically developing boys who were matched for age, gender, right- or left-handedness and IQ. The patients’ and control subjects’ behaviors were first characterized using a parent report measure of sensory behavior called the Sensory Profile.

The imaging detected abnormal white matter tracts in the SPD subjects, primarily involving areas in the back of the brain, that serve as connections for the auditory, visual and somatosensory (tactile) systems involved in sensory processing, including their connections between the left and right halves of the brain.

“These are tracts that are emblematic of someone with problems with sensory processing,” said Mukherjee. “More frontal anterior white matter tracts are typically involved in children with only ADHD or autistic spectrum disorders. The abnormalities we found are focused in a different region of the brain, indicating SPD may be neuroanatomically distinct.”

The researchers found a strong correlation between the micro-structural abnormalities in the white matter of the posterior cerebral tracts focused on sensory processing and the auditory, multisensory and inattention scores reported by parents in the Sensory Profile. The strongest correlation was for auditory processing, with other correlations observed for multi-sensory integration, vision, tactile and inattention.

The abnormal microstructure of sensory white matter tracts shown by DTI in kids with SPD likely alters the timing of sensory transmission so that processing of sensory stimuli and integrating information across multiple senses becomes difficult or impossible.

“We are just at the beginning, because people didn’t believe this existed,” said Marco. “This is absolutely the first structural imaging comparison of kids with research diagnosed sensory processing disorder and typically developing kids. It shows it is a brain-based disorder and gives us a way to evaluate them in clinic.”

Future studies need to be done, she said, to research the many children affected by sensory processing differences who have a known genetic disorder or brain injury related to prematurity.

Image1: These brain images, taken with DTI, show water diffusion within the white matter of children with sensory processing disorders. Row FA: The blue areas show white matter where water diffusion was less directional than in typical children, indicating impaired white matter microstructure. Row MD: The red areas show white matter where the overall rate of water diffusion was higher than in typical children, also indicating abnormal white matter. Row RD: The red areas show white matter where SPD children have higher rates of water diffusion perpendicular to the axonal fibers, indicating a loss of integrity of the fiber bundles comprising the white matter tracts.