Page 2 of 2

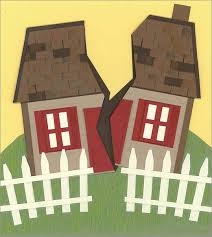

In Defense of “Broken Families”

By Ron Huxley, LMFT

I have been noticing this term “broken families” pop up a lot recently in various professional writings and parent blogs. Each time I read it, I shudder. The underlying connotation is that a family that has undergone a divorce, death, adoption, abuse, etc. is somehow broken and unrepairable. It is a fatal diagnosis that leaves families without hope. I know, I know, it’s just language but words do have power. They percolate in the brain and become belief systems and self identifying references. The more we hear the word, the more we start to belive them and then we start to give up.

When someone witnesses a teenager with substance abuse issues, for example, people will comment: “You know they come from a broken family”. Everyone who goes through foster care, adoption, or experiences a divorce is going to have mental issues, right? Wrong. Many families deal with teenage substance abuse, not just nontraditional families. While it is possible that children of divorce may act out in antisocial ways, this doesn’t mean that all children of divorce will have issues in life that impair them. The same is true for adopted children or someone in a foster home or raised by a grandparent.

I am not denying that families do suffer from going through experiences like divorce or death or adoption. Loss is central to each of these things but that should not be a life-sentence resulting in mental and relational problems. Life is full of suffering. The focus here needs to be on how to help others cope. How can we learn from those who survive and thrive and teach it to everyone. I take affront at these comments and attitudes because they assume a dark, gloomy fate just because they have undergone a loss. That is just one path.

A recent national study on foster care and adoption in the child welfare system listed that 48% of children, in the system, have significant behavior problems. At first glance, that feels devastating but what about the other 52% that don’t? Who studies them? What makes them more of a survivor, better able to cope, more reselient? Let’s see those studies. Perhaps we could learn some useful tools to help us build strong families.

My challenge is too guard our language. This means we have to closely guard the thoughts that produce them too. We have to start looking at loss for what it is, a painful experience and not as destiny. To counter these negative connotations, try identifying the strengths of families and individuals in them. What have they done well that we can build upon? What new words can we use to describe them and assume their inevitable success in life?

Kids put in institutions have different brain compositions than kids in foster care

In new research published in the journal JAMA Pediatrics, researchers looked at brain differences between Romanian children who were either abandoned and institutionalized, sent to institutions and then to foster families, or were raised in biological families.

Kids who were not raised in a family setting had noticeable alterations in the white matter of their brains later on, while the white matter in the brains of the children who were placed with a foster family looked pretty similar to the brains of the children who were raised with their biological families.

Researchers were interested in white matter, which is largely made up of nerves, because it plays an important role in connecting brain regions and maintaining networks critical for cognition. Prior research has shown that children raised in institutional environments have limited access to language and cognitive stimulation, which could hinder development.

These findings suggest that even if a child were at a risk for poor development due to their living circumstances at an early age, placing them in a new caregiving environment with more support could prevent white matter changes or perhaps even heal them.

More studies are needed, but the researchers believe their findings could help public health efforts aimed at children experiencing severe neglect, as well as efforts to build childhood resiliency.

Source:

A New Organization and a New Focus: Enabling Children and Families to Succeed

by Adam Pertman

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/adam-pertman/a-new-organization-and-a-new-focus_b_6543152.html

Finding safe, permanent homes for children in foster care – usually through adoption when they cannot return to their families of origin – has become a federal mandate and a national priority during the past few decades. That’s obviously a very good thing, but there’s a too-little-discussed downside to this positive trend: Far too little attention is being paid to serving children after placement to ensure that they can grow up successfully in their new families and so that their parents can successfully raise them to adulthood.

Notice the use of the word “successfully” twice in the last paragraph. It’s the key. It’s also the founding principle of a new organization I’m proud to lead, the National Center on Adoption and Permanency (NCAP). Our mission is to move policy and practice in the U.S. beyond their current concentration on child placement to a model in which enabling families of all kinds to succeed – through education, training and support services – becomes the bottom-line objective.

Along with fellow NCAP team members, I’ll be writing more about our organization and its goals in subsequent commentaries. For now, please check out our website and know we are already at work around the country. Furthermore, I’m delighted to announce that we’re entering into an exciting new partnership designed to significantly enhance our efforts; it is with the American Institutes for Research, one of the world’s largest behavioral and social science research and evaluation organizations. In addition, we are partnering with the Chronicle for Social Change, which like NCAP is dedicated to improving the lives of children, youth and families.

Because of the traumatic experiences most children in foster care have endured, a substantial proportion of them have ongoing adjustment issues, some of which can intensify as they age. And many if not most girls and boys being adopted from institutions in other countries today have had comparable experiences that pose risks for their healthy development.

Preparing and supporting adoptive and guardianship families before and after placement not only helps to preserve and stabilize at-risk situations, but also offers children and families the best opportunity for success. Furthermore, such adoptions not only benefit children, but also result in reduced financial and social costs to child welfare systems, governments and communities.

A continuum of Adoption Support and Preservation (ASAP) services is needed to address the informational, therapeutic and other needs of these children and their families. The overall body of adoption-related research is clear on this count: Those who receive such services show more positive results, and those with unmet service needs are linked with poorer outcomes.

(Next June, the first national conference in over a decade to focus on ASAP – which many in the child welfare community believe is the most important issue facing their field – will take place in Nashville, TN. NCAP is among the many sponsors; learn more about the event here.)

Our nation has made a concerted effort to move children into adoption and other forms of permanency because, from research and experience, we understand their value for girls and boys who cannot remain in their original homes, a value rooted in the belief that all of them – of every age – need and deserve nurturing families to promote optimal development and emotional security throughout their lives. Indeed, while child welfare systems in many states are still experiencing a variety of problems, it’s also the case that a combination of federal funding and other resources has made a significant difference – that is, they have contributed to a huge increase in the number of children moving from insecurity into permanency over the last few decades, from about 211,000 in FY 1988-1997 (an average of 21,000 annually) to 524,496 in the 10-year period ending in FY2012 (over 52,000 annually).

Furthermore, an analysis conducted by the Donaldson Adoption Institute indicates that, as a nation, we have made some progress in developing ASAP services, particularly in 17 states rated as having “substantial” programs. At least 13 states, however, have almost no specialized ASAP programs, and even the most developed of them often serve only a segment of children with significant needs. For example, many of the specialized therapeutic services have limits in duration or frequency or serve only children with special needs adopted from foster care in their own states, and some serve only those at imminent risk of placement outside their homes.

To enable families to succeed, ASAP services must become an integral, essential part of adoption. Just as the complex process of treating an ongoing health issue requires continuing care, as well as specialists who understand the complications that can arise and how to best address them, the adoption of a child with complex special needs requires specific services and trained professionals to address the challenges that arise over time.

When families struggle to address the consequences of children’s early adversity, they should be able to receive – as a matter of course integral to the adoption process, and not as an “add-on” that can be subtracted – services that meet their needs and sustain them. Adoptive families, professionals, state and federal governments, and we as a society share an obligation to provide the necessary supports to truly achieve permanency, safety and well-being for the girls and boys whom we remove from their original homes.

Given the profound changes that have taken place in the field today, especially the reality that most adoptions in the U.S. are of children from foster care with some level of special needs, permanency for them should focus on more than just sustaining their original families when possible or finding new ones when necessary. We must also provide the resources and supports that will allow them to – here’s that word again – succeed.

Get more information at http://www.nationalcenteronadoptionandpermanency.net

What It Really Takes to Raise Emotionally Healthy Kids

Interview with Dr. Jonice Webb, author of Running on Empty: Overcome Your Childhood Emotional Neglect

Eager to Adopt, Evangelicals Find Children, and Pitfalls, Abroad – NYTimes.com

Eager to Adopt, Evangelicals Find Perils Abroad

Eager to Adopt, Evangelicals Find Children, and Pitfalls, Abroad – NYTimes.com

The Ambiguous Loss Syndrome

Have you ever lost something you know still exists? Perhaps it was an old picture, a sentimental letter or your favorite pair of shoes. Initially, you search and search for the item but you cannot recover it. It eats away at you, day after day, until you are lucky enough to be reunited with it. When this happens, you give a big sigh of relief, the panic eventually subsides and you move forward with your life.

This same scenario can apply to children in the foster care system. They have been separated from what is most precious to them, their families. They know that their family members still exist, but they cannot live with them. Clearly, those children who are reunited with their families feel a great sense of relief. The children who remain in care hold onto the hope of reunifying with their families as long as they are in foster care. Their losses are unresolved.

Ambiguous loss is also known as an unresolved loss. Boss, 1999, defined ambiguous loss as the grief or distress associated with a loss (usually a person or relationship) in which there is confusion or uncertainty about the finality of the loss. There are two types of ambiguous loss:

1. When the person is physically present but psychologically unavailable. An example of this might be when a child’s parent has a mental health diagnosis or a substance use issue that makes him/her emotionally unavailable to meet the needs of the child, even if that parent is physically present.

2. When the person is physically absent but psychologically present. Examples of this would be when a child does not live with a parent due to divorce, incarceration, foster care or adoption (Boss, 1999).

For children in foster care, ambiguous loss occurs over and over again and is very difficult to process. Children who enter foster care often lose contact with their birth parents, their siblings, other family members, friends and their physical surroundings. They enter uncertain situations and are left wondering if the separation from their biological families will be permanent or temporary. Frequently, the biological family stays psychologically present in the child’s mind, even though the biological family members are not physically present. While in care, many foster children fluctuate between hope and hopelessness with regard to reunification. This is due to the ambiguous loss, which causes them to block themselves from forming healthy attachments to their new foster families. To gain a better understanding of a foster child experiencing an ambiguous loss, consider the example of this 11-year-old boy who was in foster care:

I knew that my mom kept thinking about getting us back and that helped me hang on. She told me she wanted us back. I just could never give up on my mom even though she did so much stuff. I know no matter what she put me through she still loved me. There was no way I was going to call my foster mother Mom. I got a mother. At times my mom said she couldn’t stop thinking about us and wanted to kill herself because she wasn’t with us. I thought one day she will come back and get me, wake up and realize what she did wrong. After all the pain you go through you hope there is happiness waiting for you in the end (Manuel, age 11).

Nationally, there are 463,000 children in foster care, 49% of whom are slated for reunification with their biological parents. With this in mind, it is essential that professionals working with foster children and foster parents understand the concept of ambiguous loss and work with their clients to create more stable relationships between foster parents and their foster children (www.childwelfare.gov).

How Foster Parents Can Cope Ambiguous loss can be difficult for many foster parents to comprehend if they do not have a clear understanding of its role in the foster child’s life. As outsiders, we expect the foster child to be as angry as we are at the biological parents who caused them pain. We cannot understand why the children want to have anything to do with their biological parents after being treated so badly. This may be our reality, but it is not the foster child’s reality. Extreme loyalty remains between the child and the biological family members, and hope of returning home is kept alive by phone contact or visits with biological parents who tell them that they are attempting to regain custody. These statements by parents underscore for the children that reunification is not a fantasy; it can be a reality. Since the loss is unresolved, the children find it very difficult to detach from their biological parents and attach to a new caregiver; their parents are still very much alive.

Foster parents can ease the transition for themselves and their foster children by recognizing the symptoms of ambiguous loss prior to the child entering the home. These symptoms often include: Difficulty with changes and transitions, even seemingly minor ones like sleeping in a new bed Trouble making decisions Feelings of being overwhelmed when asked to make a choice Problems coping with routine childhood or adolescent losses (last day of school, death of a pet, move to a new home, etc.) A sort of learned helplessness and hopelessness due to a sense that he has no control over his life Depression and anxiety Feelings of guilt Fear of attachment Lack of trust

(www.nacac.org). Foster parents can also help alleviate the ambiguous foster child’s anxieties and fears and create a healthy attachment by:

Acknowledging that the foster child’s biological family still exists; denial can be a real enemy. Not taking sides but spending time exploring the foster child’s feelings if he is open to this.

Giving a voice to the ambiguity – give a name to the feelings of ambiguous loss and acknowledge how difficult it is to live with this ambiguity.

Learning to redefine what it means to be a family, both foster and biological. Giving your foster children permission to have feelings about being separated from their family of origin without feeling guilty.

Helping the child identify what has been lost (the loss may not be limited to the actual parent – loss could also include the membership of that extended family, the loss of the home or town, the loss of having a family that looks like them or the loss of their family surname.

Create a “loss box.” In her work with adopted adolescents, therapist Debbie Riley guides youth as they decorate a box in which they place items that represent things they’ve lost. This gives them both a ritual for acknowledging the loss and a way for them to revisit the people or relationships in the future.

Creating a life book and writing in the birthdays and names of their biological family members. Understanding that sometimes certain events trigger feelings of loss, such as holidays, birthdays or the anniversary of an adoption.

Alter or add to family rituals to acknowledge the child’s feelings about these important people or relationships that have been lost. For example, adding an extra candle representing the child’s birth family on his or her cake may be a way of remembering their part in your child’s life on that day.

Don’t set an expectation that grief over ambiguous loss will be “cured,” “fixed” or “resolved” in any kind of predetermined timeframe.

Explain that feelings related to ambiguous loss will come and go at different times in a person’s life and provide a safe place for the child to express those feelings (www.nacac.org).|

In addition to unconditional love, the best gifts that anyone can give a foster child coping with an ambiguous loss are patience, honesty and acknowledgement.

References Boss, P. (1999), Ambiguous Loss. Learning to live with unresolved grief. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. National American Council on Adoptable Children. (2011). Retrieved October 2, 2010, from www.nacac.org/links.html

Share your thoughts on this issue by posting your comments on http://www.facebook.com/parentingtoolbox

GraceSLO: Adoption & Foster Care Conference

Hear Ron Huxley, founder of the ParentingToolbox.com, and many other Central Coast speakers talk about Adoption and Foster Care from a Faith-Based Perspective:

Attachment Disordered Children – Radio Show Interview with Ron Huxley

If you didn’t catch my radio show interview this morning you can listen to the archived mp3 at http://toginet.com/shows/theparentsplate/articles/1314 Brenda Nixon, host of the Parents Plate radio show, invited me to chat about the controversial diagnosis of Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) and the current state of mental health treatment of traumatized children today. I shared some great ideas in our hour long discussion that you will want to listen in on…everything from how children are diagnosed to attachment neuroscience to practical parenting tools. I even shared on why children with attachment impairments “Monster Up!” – a phrase I coined. Take a moment to download or stream the show at http://toginet.com/shows/theparentsplate/articles/1314

How can you punish an abused child?

I recently watched a movie called “Unthinkable” (CAUTION: Movie spoilers ahead) and was shocked by the intensity of the violence. At first I turned it off then later went back to finish watching the movie. There was something about the plot line that drew me back in. The subject matter was simple: A terrorist sets up nuclear bombs throughout America, is captured, and then tortured to tell their locations. Yes, tortured. Aside from the more obvious political messages here, there was a subtler, frightening psychological message.

No matter how much the terrorist was tortured physically or mentally he never broke. He suffered but he continued to play mind games with this capturers till the very end. What would hold a person together despite such horrific punishments? I realized what the answer to this question was when the terrorist stated that “he deserved this” for all the bad things he had done. The movie never really described what these “bad things” were but it was enough of a mindset for him to endure unbelievable torture. His captors tried everything to break him: reason, empathy, brutality, mind games, more brutality and finally more brutality. They just kept upping the ante on the terrorist with the belief that eventually everyone breaks. He didn’t.

What struck such a cord in me was that many of the children I work with, who have been mistreated, have this “terrorist” mindset. Their behavior says: “What can you possibly do to me that I have not already endured in a much younger, more vulnerable state as an infant or young child?” So many of the children who adopt this “defiant” attitude have a deeper narrative that they deserve the punishments they are getting. Children internalize their abuse and believe that they are responsible for what happened to them. In fact, they often believe that they are “damaged goods” unworthy of love or kindness or anything good. They may set up caregivers to make them angry and want to punish them. It is easy for an adult caregiver to play right into this narrative and reinforce the very thing they want to change in the child. They may not beat them or leave them in a closet for days but we do use other punishment-based techniques (lock them up, move them from home to home, shame them with words or actions, make them carry out sentences, etc) all with the hopes that they will express their guilt and shame and change their behaviors.

I think the end goal is a worthy one. We want to help the child see things differently but our methods need some updating. Hope for this is coming from the field of neuroscience which is why you will see so much of this in this blog. It may not be the final answer but it is allowing us to see the small, hurting child behind the big terrorist mask. It is telling us that children’s brains and minds are affected by their mistreatment and we must go back and redo attachment-based treatments to help them rebuild the mental and physical capacity for love and affection and moral reasoning too.

I know it sounds like I am hard on the adult caregivers. I guess I am but we are the ones who have to do something different. We can’t expect the child to “get it” and explain it to us. We have to look deeper to see the alternative narratives for the child to live out. That will take time and patience. Unfortunately, we caregivers are products of our own culture and parenting narratives. A shame-based approach to parenting is how many of us were raised and so, it is the only approach we know how to use. If time out for an hour in a child’s room doesn’t work, what else is there? More time in the room? Perhaps we should yell louder or threaten more? Obviously not. The answer to my title: How can you punish an abused child, is simple. You can’t.

The mission of the Parenting Toolbox blog is to give parents more tools. I used to teach a lot of court-ordered parenting classes where parents where referred to learn non-punitive parenting skills. I quickly learned that you got no where trying to debate the punishment mindset. I realized that I couldn’t really win the “spank/no spank” argument. I might get some compliance from the parent but there was no change in insight. My focus became teaching other things the parent could do by giving lots of parenting tools. This worked. It is my vision to see parents better equipped and hurt children healed with this blog as well.

* Get some power parenting tools in our new premium newsletter. Subscribe today!