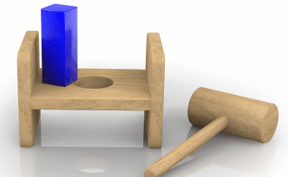

Does your child seem like a “Square Peg in a Round Hole”?

When Your Child Doesn’t Seem to “Fit”: Understanding and Supporting Neurodivergent Kids

Picture trying to fit a square block into a round hole in a shape sorter. No matter how hard you push or turn it, it just won’t fit. This is how many neurodivergent children feel every day in schools, social situations, and even at home. These are the kids who might have ADHD or autism or simply think and experience the world differently than most. But here’s the thing – they’re not broken blocks that need reshaping. They’re unique individuals who need the right space to shine.

“Why Can’t My Child Just…?”

If you’ve ever asked yourself, “Why can’t my child just follow simple directions?” or “Why do they struggle with things other kids find easy?” you’re not alone. Dr. Ross Greene, who has worked with countless families, puts it beautifully: “Kids do well if they can.” This simple but powerful idea turns traditional thinking on its head. When our children struggle, it’s not because they’re being difficult – it’s because something in their environment doesn’t match their needs or abilities.

It’s Not About Trying Harder

Consider asking someone nearsighted to “just try harder” to see clearly. Sounds ridiculous, right? Yet we often expect neurodivergent kids to “try harder” to fit into situations that aren’t designed for their way of thinking or processing information.

Robyn Gobbel, who specializes in helping parents better understand their children, explains that connecting with our kids is more important than trying to correct their behavior. When children feel understood and supported, they’re much more likely to develop the skills they need to navigate challenging situations.

Your Child’s Brain: A Different Kind of Beautiful

Dr. Daniel Siegel helps us understand that every child’s brain develops in its own unique way. Just like some people are naturally artistic while others are mathematical, neurodivergent children have unique ways of thinking and learning. Instead of seeing this as a problem to fix, we can view it as a different kind of gift to nurture.

Making Room for All Shapes

So, how can we help our square pegs thrive in a world full of round holes? Here are some practical ideas:

- Create “just right” challenges: Break big tasks into smaller, manageable pieces

- Look for the message behind the behavior: When your child struggles, ask, “What’s making this hard?” instead of “Why won’t they cooperate?”

- Celebrate different ways of doing things: Maybe your child needs to move while learning or draw while listening.

- Trust your instincts. You know your child best. If something isn’t working, it’s okay to try a different approach.

A New Way Forward

Instead of trying to make our children fit into spaces that weren’t designed for them, we can work on creating spaces that welcome all kinds of minds. This might mean:

- Talking with teachers about flexible learning options

- Finding activities where your child’s unique traits are strengths, not challenges

- Connecting with other parents who understand your journey

- Most importantly, helping your child understand that different isn’t wrong – it’s just different

The Real Goal

The goal isn’t to turn square pegs into round ones. It’s to create a world where all shapes are welcomed and valued. Your child isn’t a problem to solve – they’re a person to understand and support.

Recommended Resources

For parents wanting to learn more:

- “The Explosive Child” by Dr. Ross Greene

- Learn about collaborative problem-solving and working with your child instead of against them

- “Lost at School” by Dr. Ross Greene

- Understanding how to advocate for your child in educational settings

- “The Whole-Brain Child” by Dr. Daniel Siegel and Dr. Tina Payne Bryson

- Practical strategies for understanding your child’s development and behavior

- “Beyond Behaviors” by Mona Delahooke

- Understanding and helping children with behavioral challenges

- “Building the Bonds of Attachment” by Daniel Hughes

- Insights into connection-based parenting approaches

Online Resources:

- Lives in the Balance (Dr. Greene’s website): http://www.livesinthebalance.org

- Robyn Gobbel’s parenting resources: http://www.robyngobbel.com

- Dr. Siegel’s Mindsight Institute: http://www.mindsightinstitute.com

Remember, you’re not alone on this journey. These resources are here to support both you and your child as you navigate this path together.