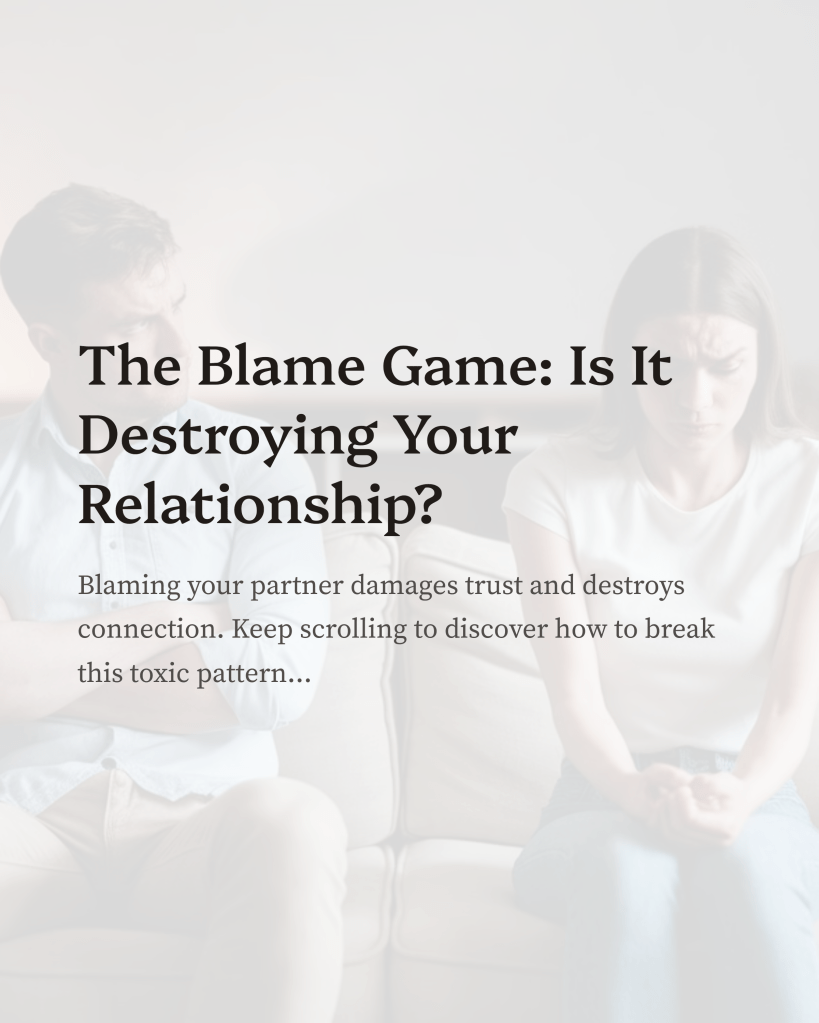

Outside the Circle: How One Couple Learned to Step Back from the Magnetic Pull of Conflict

Imagine a circle drawn on the ground. Inside this circle, two people are locked in an ancient dance—circling each other, taking turns being pursuer and pursued, accuser and defender. The circle is magnetic, hypnotic. Once you step inside, the gravitational pull becomes almost irresistible.

This was Mark and Sarah’s marriage for three years.

The Circle of Conflict

“You promised you’d load the dishwasher,” Sarah said, her voice carrying that familiar edge that made Mark’s shoulders tense. “But here I am, coming home to the same mess again.”

Mark felt it immediately—that invisible force pulling him into the circle. His body moved toward the familiar position: feet planted, arms crossed, jaw set. “I was going to do it. You never give me a chance to—”

And there they were, both inside the circle again, spinning in the same exhausting pattern. Sarah feeling unheard and unsupported. Mark feeling criticized and trapped. Round and round they went, each movement predictable, each response drawing them deeper into the magnetic field of their conflict.

From inside the circle, each could only see the other as adversary. From inside the circle, each felt completely justified in their position. From inside the circle, there was no escape—only the endless dance of attack and defense.

The View from Outside

Three months earlier, Mark’s therapist had drawn an actual circle on a piece of paper during their session.

“This is where you and Sarah spend most of your time,” she said, pointing to the inside. “When you’re in here, you can only see each other. You can’t see the pattern you’re trapped in. You can’t see that you’re dancing the same dance that millions of couples dance.”

She drew a larger circle around the first one, then another around that.

“But what if you could step outside? What if you could observe the dance instead of being trapped in it? What if you could see that this isn’t actually personal—it’s just two people caught in a very old, very common pattern?”

Mark stared at the concentric circles. “But how do you step outside when everything in you is being pulled back in?”

The Magnetic Pull

The next time Sarah criticized him, Mark tried to observe what was happening in his body. The pull was immediate and powerful—like standing at the edge of a whirlpool. His chest tightened. His breathing changed. Every cell in his body wanted to step into the circle and defend himself.

“You always do this,” Sarah continued, her voice rising. “You make promises and then—”

Mark could feel himself being drawn in. The circle was calling to him. Defend yourself. Explain. Make her understand. Fight back.

But instead of stepping in, he tried something unprecedented. He imagined himself taking a step back. Not physically—he stayed right where he was—but energetically. As if he were observing the scene from outside the circle.

From this vantage point, he could see something remarkable: Sarah wasn’t his enemy. She was someone in pain, circling inside the same trap he’d been circling in. She was caught in the magnetic field just as much as he was.

“I can see you’re really frustrated,” he said quietly.

Sarah stopped mid-sentence, clearly expecting him to step into the circle with her. When he didn’t take the bait—when he didn’t defend or counter-attack—the dance had nowhere to go.

The Power of the Pattern

For Sarah, staying outside the circle proved even more challenging. She had years of practice stepping into conflict, and the pull was magnetic in a different way. When Mark didn’t fight back, when he didn’t give her the resistance she expected, she felt disoriented.

“Why aren’t you defending yourself?” she asked, genuinely confused.

“Because I can see what’s happening,” Mark said. “We’re both about to step into that circle again. And I’ve started to notice that nothing good ever happens in there.”

But Sarah could feel the gravitational pull intensifying. He’s trying to avoid responsibility. He’s using some therapy trick to make me look like the crazy one. The circle was calling to her, and everything in her wanted to pull him back in with her.

“Don’t you dare therapize me,” she snapped.

Mark felt the familiar tug—the irresistible urge to step into the circle and defend his new approach. The magnetic pull was strongest when Sarah was trying to drag him back in. But he held his position outside the circle.

“You’re right to be suspicious,” he said. “I would be too. But I’m not trying to avoid responsibility. I’m trying to see what’s really happening between us.”

Learning to Observe

Gradually, Sarah began to experiment with stepping back herself. It was harder for her because she had learned early in life that stepping into conflict was how you got your needs met. Staying outside the circle felt dangerous, like giving up.

But one evening, when Mark forgot to pick up their daughter Emma from soccer practice, something different happened. Sarah felt the familiar rage—the magnetic pull toward the circle of blame and defense. But this time, instead of immediately stepping in, she paused.

From outside the circle, she could see the larger pattern: Mark, probably feeling terrible about his mistake, preparing to defend himself. Herself, feeling overwhelmed and unsupported, preparing to attack. The same dance they’d been dancing for years.

She could see something else too: how this exact scene was playing out in thousands of homes across the country. How universal this pattern was. How impersonal, really, despite feeling so intensely personal.

When Mark came home full of apologies and excuses, Sarah didn’t step into the circle.

“I can see you feel awful about forgetting,” she said instead. “And I can see that I’m about to make you feel worse. What if we don’t do our usual dance this time?”

The Larger Circles

As Mark and Sarah practiced stepping outside their personal circle of conflict, they began to see ever-widening circles around them. The circle of couples having the same fights. The circle of humans struggling with the same needs for appreciation and understanding. The circle of all beings trying to love and be loved imperfectly.

“When I can see that our fight isn’t just our fight—that it’s the fight that every couple has—it feels less intense,” Sarah explains. “Less like life or death. More like… just what humans do.”

Mark learned to recognize the early warning signs of the circle’s magnetic pull: the tightening in his chest, the urge to explain and defend. “Now when I feel that pull, I imagine taking a step back. Not away from Sarah, but away from the pattern. I can stay present with her while refusing to dance the old dance.”

The Resistance

Stepping outside the circle wasn’t always welcomed by their dynamic. The pattern itself seemed to fight back, as if it had a life of its own.

“There were times when one of us would stay outside the circle, and the other would get more intense, trying to pull them back in,” Sarah remembers. “It’s like the pattern needed both of us to keep it alive.”

The children noticed too. Emma, their thirteen-year-old, actually complained when her parents stopped fighting in their familiar way. “You guys are being weird,” she said. “Why aren’t you yelling at each other?”

Even friends and family members seemed unconsciously invested in the old pattern. “Sarah’s finally training you, huh?” a friend joked when Mark started responding differently to criticism. The comment felt like an invitation to step back into the circle.

The View from Above

Six months into practicing this new approach, Mark and Sarah describe their relationship differently.

“We still trigger each other,” Mark says. “But now when it happens, instead of getting sucked into the vortex, we can usually observe what’s happening. We can see the circle forming and choose whether or not to step into it.”

Sarah nods. “And most of the time now, we choose not to. Because we’ve seen what’s in there—just the same old dance that never resolves anything. Why would we keep going back?”

They describe a strange phenomenon: the more they stayed outside their personal circle of conflict, the more they could see the larger circles of human suffering and struggle. Their individual pain became part of something much bigger, much more universal.

“When you realize that every couple who has ever lived has struggled with feeling heard and valued, your specific fight about the dishes becomes… well, it becomes workable,” Sarah explains. “It’s still important, but it’s not the center of the universe anymore.”

The Practice

For couples willing to experiment with stepping outside the circle, the practice requires constant vigilance:

Recognize the Pull: Learn to identify the physical sensations that signal you’re being drawn into the circle—tension, heat, the urge to defend or attack.

Step Back: Imagine taking a literal step backward, moving from participant to observer. Ask yourself: “What pattern are we about to dance?”

Expand the View: See your conflict as part of larger circles—all couples, all humans, all beings struggling with the same basic needs.

Stay Present: Remaining outside the circle doesn’t mean checking out. You can be fully present with your partner while refusing to dance the old dance.

Expect Resistance: The pattern will try to pull you back in. Your partner might intensify their attempts to engage you in the familiar dance. Hold your position.

The Paradox of Distance

The paradox Mark and Sarah discovered is that by stepping outside their circle of conflict, they actually became closer. When they stopped seeing each other as adversaries in a battle, they could see each other as fellow travelers caught in the same human predicament.

“We thought stepping back meant caring less,” Mark reflects. “But it actually means caring more effectively. When I’m not trapped in the circle, I can actually help Sarah with what she’s struggling with instead of just defending myself.”

The magnetic pull of their old pattern still exists. The circle is still there, still calling to them. But they’ve learned that they have a choice. They can observe the dance instead of being trapped in it. They can see the larger patterns instead of being hypnotized by the personal drama.

And in that space outside the circle—in that place of expanded awareness—they’ve found something they never expected: the freedom to love each other without needing to fix each other, to be present without needing to be right, to connect without needing to control.

The circle of conflict is still there. But they’re learning to live in the larger circles of compassion, understanding, and shared humanity. And from that vantage point, everything looks different.